There’s something satisfying about tweaking and refining a product. Over the last few years, I’ve been making my blog progressively faster.

It’s been more of a passive, than an active task. I just chip away at certain parts when I find a new technique, or I feel a part of the site needs improvement. I’ve FLIPped my animations to make them more performant. I’ve set smarter caching in my nginx config. I even minified my HTML (every little helps). But recently I made a change that took my load time from an already impressive 600ms, and halved it. To put that in perspective, it takes around 350ms to blink your eye. It loads that fast that if you blink, you’ll miss it. This gets even more impressive when you throttle the connection. On a regular 2G connection my site would load in just under 2 seconds. That’s not too bad, but after my most recent update I got that time down to 300ms. Yep, 300ms on even the slowest of internet connections. In fact, to go one further, it even loads when the connection is so slow, it doesn’t exist. 300ms to load the site, when you’re completely offline.

If you hadn’t worked it out yet, I’ve just added a service worker to my site. As far as service workers go, this one is pretty simple. Once it’s installed, it caches the most used files on the site; the JS, CSS, and index.html. If you then visit any of the articles, it caches them as well. This allows us to design for an offline first experience. Let me show you how it’s done.

Setting the right environment

First off, in order to run the service worker, we need to add SSL certificates on our website. I used let’s encrypt because it was free and I could get it up and running relatively quickly. There are lots of other ways to do it, choose whatever works best for you. As long as we have an SSL cert and can serve our site over https:// , we’re golden.

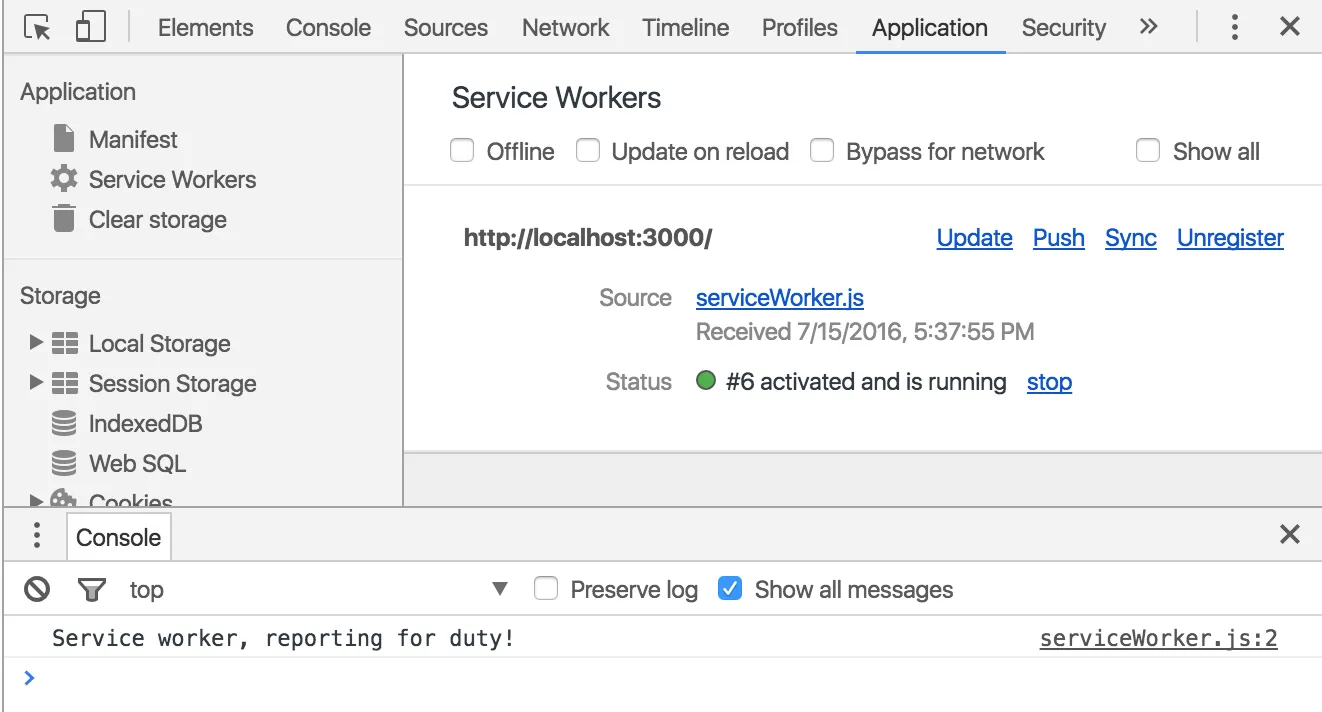

If you’re just running this locally, you don’t need to worry about this step. I would recommend using Chrome Canary as (at the point of writing this) there’s a lot more tools for debugging the service worker. You’ll find them all under the ‘Applications’ tab in developer tools.

Installation

So, we’ve got our secure environment set up, we need to install our service worker. Let’s create a simple javascript file that notifies us of it’s presence.

console.log("Service worker, reporting for duty!");

Next up, we have to install the service worker. Just pop the following block into your main javascript file and be sure to update the path to your service worker.

if (navigator.serviceWorker) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register("/path/to/serviceWorker.js", {

scope: "/",

});

}

Include this script somewhere on your page and it should find the service worker and install it. Notice we’ve wrapped the function in an if statement. This just checks the browser supports service workers before trying to install one. If the support isn’t there, the service worker doesn’t get installed and the website goes about it’s day as if nothing happened. Progressive enhancement, done.

If this is all set up correctly, you should see a message from your service worker in the console. If you navigate to the application tab in developer tools you should see the service worker ticking away as well.

We’ve installed our service worker, but it doesn’t do a great deal. Let’s hook into the install event and start caching pages.

self.addEventListener("install", (event) => {

event.waitUntil(

caches

.open("static-v3.5.1") // Namespaced on site version number

.then((cache) =>

cache.addAll([

"/scripts/vendor/modernizr.js",

"/scripts/main.js",

"/css/screen.css",

"/wrote",

])

)

);

});

Let’s break this down. First off, we hook in to the install event. event.waitUntil() tells our service worker to wait until all the actions inside that function are completed before finishing the install process and moving into the installed state.

The installation we wish to perform is to store all the pages we want to cache. caches.open('static-v3.5.1') opens a cache named static-v3.5.1 . Using promises, and .then() I added my css, js and a couple of key pages to the newly opened cache.

That’s the installation process done. Like any other installation process, it only has to be done once. If we reload this page, this process gets skipped as we’ll already have all our files in the cache. This is where we run into our first problem, cache invalidation.

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things. — Phil Karlton

The plan for this service worker is to serve the files from the cache, instead of requesting them from the server. We haven’t told it to do that yet, but it creates a problem that is best fixed early on. Let’s say we update our site’s CSS file. When we refresh the page, the service worker kicks in and loads the cached CSS file, which is now out of date. Bugger.

Luckily, Chrome has us covered. Just jump back into the service workers tab we were in earlier and hit, [] update on reload . This will cause Chrome to reload the service worker and re-install itself when you refresh the page, bringing the updated files into the cache. However, we can’t set this flag on our users’ browsers. This is why I used the version number of my site when I created the cache. Because I use semver, I can be sure that any releases to my site will have a different version number, and therefore a different service worker cache. When I update the site, you initially see the old one whilst the new one installs in the background. Then the next time you load the site, the new one is all ready and waiting in the new cache for you. This does mean we need to do a little housekeeping, but we’ll get to that later. Back to the good stuff!

Request hijacking

The service worker is installed, the files are cached, our service worker is primed and ready. This is where the real magic of the service worker comes in to play. Normally, when a browser requests a file it goes straight off to the server. The server hears the request, finds the requested file, and sends it back to the browser. With a service worker, you can intercept this request.

self.addEventListener("fetch", (event) => {

event

.respondWith

// Response goes here...

();

});

We start off by listening for the fetch event, then we hijack the response with event.respondWith() . At this point we could return anything and the browser will act as if the request went through as normal. Want to listen for all the image requests and swap them out with pictures of Nick Cage? You can. However, we need something more practical.

event.respondWith(

caches

.match(event.request)

.then((response) => response || fetch(event.request))

);

caches.match(event.request) goes and checks our cache for the page that’s being requested. If the cache has our page, response becomes truthy and we serve up the page from the cache. If the page isn’t in the cache, response is falsy and we return the original fetch event for the page. This line may look a little confusing, but it’s really just shorthand for:

.then(function(response) {

if (response) {

return response

} else {

return fetch(event.request)

}

})

If all goes well, we should be successfully serving our pages from the cache. This is the key to making our site blazing fast on even the spottiest of connections.

Cleaning house

We tackled the majority of the caching issues earlier, but you’ll soon notice a problem. After a while our caches start building up. We’ll have the current version’s cache, but we’ll also have a load of obsolete caches from previous versions. We never access them, so it’s only right we clean them up. It’s rumoured that this is a feature that will be coming to service workers in the future, but for now we can do it ourselves:

const currentCache = "static-v3.5.1";

self.addEventListener("activate", (event) => {

event.waitUntil(

caches.keys().then((cacheNames) => {

return Promise.all(

cacheNames.map((cacheName) => {

if (currentCache !== cacheName) {

return caches.delete(cacheName);

}

})

);

})

);

});

This is mostly taken from Jake Archibald so all credit goes to him for this one. In fact, I’m pretty sure we can credit the majority of the service worker spec to him. If you wanna look into service workers, look into Jake.

Optional extras

This is all you need to get started with service workers, but there’s a lot more you could do. I’ve added a few optional extras to my service worker, feel free to take a look at it. These work really well with a good manifest file and are the backbone of the progressive web app movement. As ever, have a play about with them and see what you can do.

Comments

(Powered by webmentions)Start the Conversation